As an initial blog entry, I’m going to toot my own horn – my new book, which appeared a few weeks ago with UNC Press.

As an initial blog entry, I’m going to toot my own horn – my new book, which appeared a few weeks ago with UNC Press.

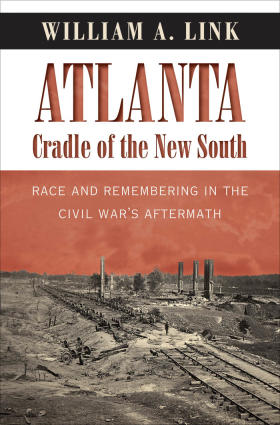

The book charts out how Atlanta became a place where the “New South” was defined, but how that occurred only in the context of the aftermath of the Civil War. I begin with antebellum Atlanta, how it grew into a significant town by 1861, how the Civil War transformed the city, but also how the war brought invasion and destruction as a result of William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, May-September 1864. The retreating Confederates burned the city, and so did Sherman when he left in November 1864.

A significant piece of the story is how Atlanta was destroyed, but then how it remade itself – by consciously embracing images of destruction as part of a new narrative of rebirth. The rehabilitation of Atlanta led to its definition, ultimately to the social construction of the “New South.”

The notions of what the Civil War meant and how it was remembered was an active, living things for Atlantans, because it portended so much about their future. This was especially true for African Americans, who made Atlanta into a base for strong leadership in the postwar era. Black Atlantans contested the standard southern white account of what the war meant, offering instead a very different narrative.

The book ends with the infamous Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, which is a well-told story, but not in this context – as part of the living memory of Civil War’s aftermath. In one of the worst examples of racial violence in the early 20th century urban South, two visions of Atlanta and of the New South came face to face.